8 Social Policy: Crisis and

Transformation

Peter Katzenstein (1987, pp. 168-92) portrayed the West

German wel-

fare state as a highly segmented polity governed by

consensual politics

and providing generous social benefits. In fact, at first

sight, not much

has charged during the past two decades: compulsory

insurance for all

wage earners (sozialversicherungspflichtige

Beschäftigung)

is still provided

by separate funds for pensions, health, unemployment,

occupational

accidents and - since 1995 - nursing care for the elderly

(Pflegeversicher-

ung). The system is still highly fragmented, with

provision determined by

a person's region of residence as well as by that person's

occupation.

Thus, several regional funds are in charge of pensions for

blue-collar

workers (Arbeiter), whereas pensions for white-collar

employees (Anges-

tellte) are funded on a national basis. Civil servants

(Beamte) receive their

old-age benefits from current state budgets, while other

public-sector

employees are covered by the national white-collar

workers' insurance

scheme, supplemented by a complementary insurance which

puts them

on a par with civil servants. There is an entirely

separate pension scheme

altogether for coal miners, and finally, self-employed

persons (Selbststä n-

dige) are allowed to opt out of the system altogether,

which they normally

do, since private pension and medical providers normally

offer better

levels of cover at lower costs than do the statutory

schemes.

Health insurance too still rests on a multitude of local,

regional and

national institutions. Although employees have been free

to choose their

health insurance fund since 1996, which has inevitably

weakened the

linkage to occupational status, the federal government has

introduced a

portfolio balance system to support those funds with bad

risks. These are

usually the old established local blue-collar workers'

general health

funds (Ortskrankenkassen), which were founded in the 1880s

as part of

Bismarck's welfare initiative to attract workers away from

trade union-

led health funds (Katzenstein 1987, p. 172). None of these

insurance

schemes is capital-based; instead they all rely on current

inflows of

social-security contributions to meet their commitments

(the so-called

"pay-as-you-go" system). Inevitably this makes the system

particularly

165

vulnerable to economic downturns, which immediately open

up a

revenue-outlay gap.

Both employees and employers still share most of the costs

of social

security by each paying an equal proportion of the

employee's salary as

a compulsory social-insurance levy. Apart from

work-related compul-

sory insurance schemes, a number of additional

tax-financed social

programmes are run by state, federal and local

governments. These are

meant to provide for social needs that fall outside the

remit of

the compulsory insurance funds, such as child benefit

(Kindergeld),

home construction grants (Eigenheimzulage) and grants for

higher edu-

cation (BAFöG). In consequence, welfare allowances

are

available in

some form to almost everyone resident in Germany (cf.

Katzenstein

1987, p. 186). However, in recent years state subsidies to

these funds

have steadily increased. The total share of general

government contribu-

tions (that is, tax-financed contributions) to

social-security programmes

rose from 26.9 per cent in 1991 to 32.5 per cent in 2000.

In 1999, an

eco-tax was introduced to generate extra resources for the

ailing old-age

pensions system (cf. chapter 10 in this volume). During

the 1990s, total

employee contributions to social-security programmes

remained con-

stant at around 28 per cent of the total income for these

programmes,

whereas the total employers' contributions decreased from

42.5 per cent

to 36.9 per cent (Eurostat 2003, p. 7). Yet despite the

increase in

state (i.e. tax-based) funding for these programmes,

statutory social-

insurance contributions have exceeded 40 per cent of the

average gross

salary since the mid-1990s (Hagen and Strauch 2001, p.

24). Not

surprisingly, the subject of social-security contributions

has become a

hotly debated topic, especially as Germany is the only

country that still

levies such contributions at such a high level on

employers. It has

been argued that these non-wage labour costs have both

exacerbated

Germany's unemployment problem, by making it prohibitively

expen-

sive to employ new staff, and compromised the

international competi-

tiveness of German companies. Politically, therefore, one

of the major

goals of welfare-state reform policies since the mid-1990s

has been to

reduce the very high level of non-wage labour costs (in

other words, the

social-security contributions levied on employees and

employers).

During the 1990s, the German welfare state ran into deep

trouble.

However, remedial action has been limited to incremental

reductions in

the costs and benefits of welfare programmes, and, in

particular, to a

shift towards a greater degree of tax funding for such

programmes. Yet,

despite its persisting institutional structure, the

welfare state has

changed considerably in terms of its financial flows,

political-power

structures, scope of services and general policy concepts.

When

166

Roland Czada

compared with Peter Katzenstein's portrayal of 1987, the

situation in

2004, with acute political conflicts and considerable

benefit cuts, indi-

cates a welfare state in transition. Traditional features

of social corpor-

atism, such as party consensus and work-related

paternalism, have been

superseded by new forms of decision-making, including

corporatist

technical advisory commissions, issue-specific (and hence

volatile) party

alliances, the emergent use of market principles and a

more universalistic

approach to the funding and delivery of welfare benefits.

Although this

transition has by no means been completed, its driving

forces, which will

be addressed in the next section, are clearly visible.

Context: the "German Model" and the Challenge of

Unification

Two distinct factors make up the context of these recent

policy chal-

lenges to the German welfare state. The first can be

traced back to the

so-called "German Model" of forced industrial

modernisation policies;

the second stems from the unification of the economically

weak socialist

German Democratic Republic with the still prosperous

Federal Repub-

lic of Germany. Of course, the German welfare state has

not been

insulated from broader pressures of globalisation and

demographic

changes; however, because of their general character,

these will be

discussed separately later in this chapter.

As chapter 7 has shown compellingly, Germany"s

social-security funds

have been used from the 1970s onwards to compensate

generously those

large segments of the workforce who fell victim to the

gradual process of

industrial modernisation and restructuring. Faced with

rising unemploy-

ment from the mid-1970s onwards, Germany simply

transferred its

least-productive sections of the workforce into the

welfare system, in

stark contrast to both the American and British social

workfare policies

and the Scandinavian active reintegration programmes. A

corporatist

productivity coalition of unions, employers and the state

agreed to

exploit the then buoyant social-insurance funds to finance

early retire-

ment for older workers and to facilitate companies'

efforts to rationalise

the least-qualified and least-productive elements of their

workforces. An

Early Retirement Act (Vorruhestandsgesetz) was passed in

1984, and a

Law on Part-Time Work for the Elderly

(Altersteilzeitgesetz) followed in

1988. In a collaborative effort, employers and works

councils (Betriebs-

räte) helped to implement these laws, which overall

were

very effective

(Table 8.1). The Federal Labour Office (Bundesanstalt

für

Arbeit, BA)

was given the task of financing both measures from its

unemployment

insurance funds, supplemented by some additional federal

grants.

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

167

However, because the BA's financial responsibility was

from the outset

limited until 1988, the pension schemes were faced with a

double

challenge in the early 1990s, when they had to absorb not

only large

numbers of pensioners in western Germany who had retired

early, but

also - following unification - all pensioners in eastern

Germany.

Self-evidently, a German-style pay-as-you-go system, under

which

wage earners' contributions are almost immediately

transferred to pen-

sioners as cash benefits, is particularly sensitive to a

relative decline in

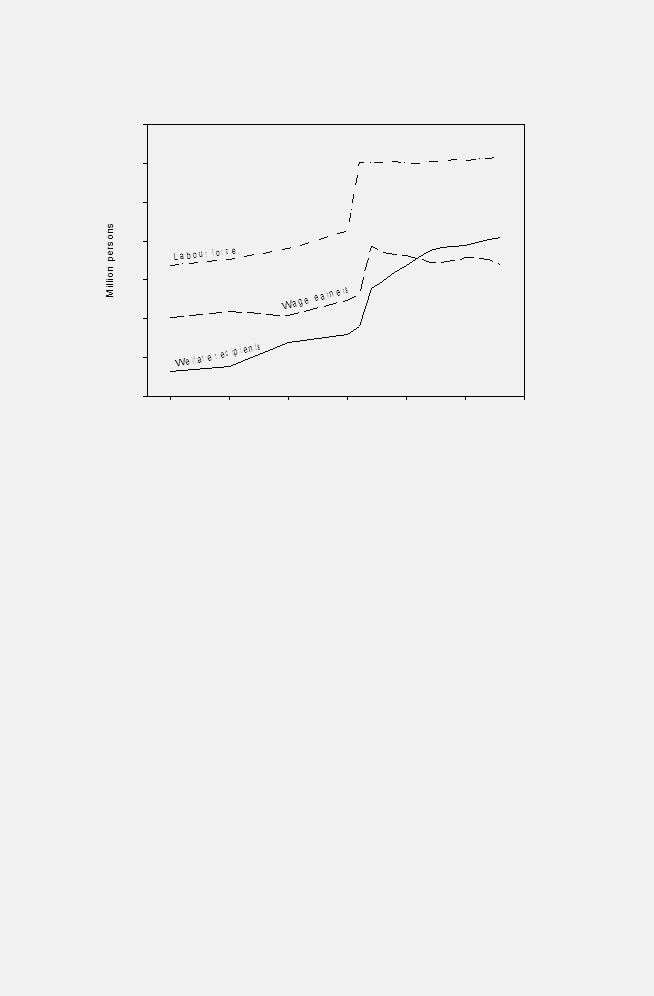

regular employment. For 2001, the Federal Statistical

Office (Statis-

tisches Bundesamt) reported 27.817 million wage earners

compared with

26.735 million persons living on social-security income

(Figure 8.1;

Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Soziale

Sicherung

2004). By

comparison, the respective numbers for 1985 were 20.378

million wage

earners contributing social-insurance fees, against 13.485

million per-

sons living on welfare. As a result, the ratio of wage

earners to welfare

recipients has fallen from 1.5:1 in 1985 to 1:1 in 1997,

and in 2003 stood

at just 0.9:1.

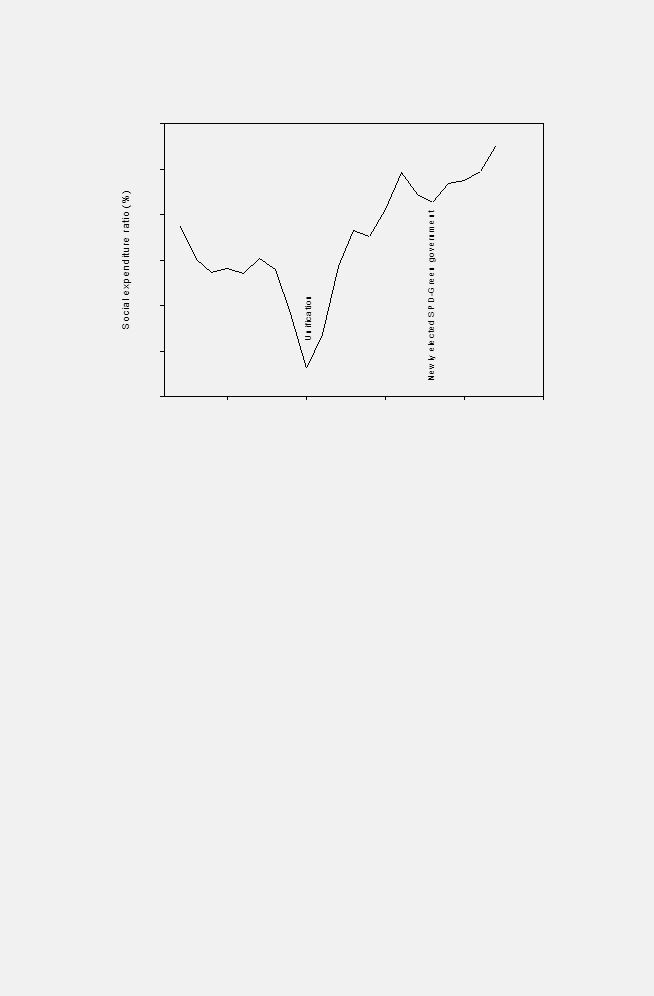

Figure 8.1 shows that the number of wage earners paying

social-

security contributions has declined steadily since

unification. Although

this has principally been caused by large-scale job

losses, mainly in

eastern Germany, from 1992 onwards, the peculiarities of

the welfare

state have themselves also been responsible. Until

recently, employment

policies were focused entirely on measures to create a

skilled workforce

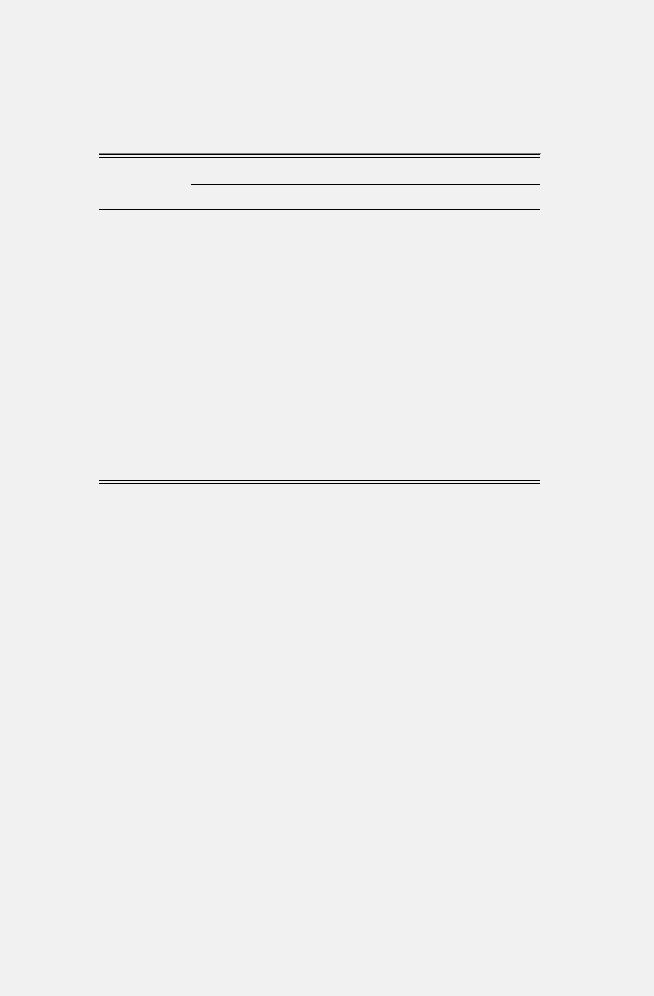

Table 8.1. Growth of early retirement, 1975 - 99

Average age of

new pensioners

retiring due to

unemployability

New pensions for formerly

unemployed persons

(% of all new pensions)

Unemployable

early retirees

(% of all

pensioners)

Western

Germany

Eastern

Germany

Year

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

West East

1975

56.3 59.2

3.7

0.7

3.5

1980

54.7 57.7

8.4

1.6

4.8

1985

54.8 54.3

11.9

1.1

7.9

1990

53.9 52.6

13.7 1.8

10.7

1995

53.5 51.4

24.2 3.4

60.2 6.4

8.7 10.2

1999

52.9 50.8

26.9

2.1

54.5 1.8

14.4 31.4

Source: Hagen and Strauch 2001, p. 17.

168

Roland Czada

and to enhance productivity, rather than on job creation

in low-skill (and

low-income) areas. Although tax cuts for low-income groups

had been

introduced in 1996 following a ruling by the

Constitutional Court, this

did not create any new incentives for recipients of income

support to find

work. Until the end of 2004, for an average-sized family,

employment of

any sort meant a withdrawal of benefits, meaning that

overall net income

often either stayed the same or was even lower than the

level of benefits.

Nonetheless, despite a declining number of wage earners

who are

subject to social-insurance contributions, Figure 8.1 also

shows that the

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000 2005

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Figure 8.1. Labour force, wage earners and welfare

recipients (1975-200)

Note : The labour force

includes all persons engaged in economic activity

working regular weekly hours (paid civilian and military

employment,

self-employment and unpaid family workers) plus all those

unemployed

but seeking work. Wage

earners pay compulsory social insurance fees

(sozialversicherungspflichtige Beschattigung). Welfare

recipients are defined

as persons living solely from social security income,

including old age

pensioners (who receive Arbeiter-, Angestellten und

Knappschaftsrenten),

recipients of unemployment support

(Arbeitslosengeld-und-hilfe), recipi-

ents of income support (Sozialhilfeempfänger) and

asylum

seekers (Asyl-

bewerber). Not included are welfare recipients living on

accident

annuities (Unfallrenten) and students's grants as well as

workers in

training and job creation schemes.

Source : Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Soziale

Sicherung 2004.

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

169

total labour force, which measures the number of people

who are eco-

nomically active or seeking work, has grown considerably

between 1975

and 2003. In the first instance, this was a result of the

growth of

Germany's population after unification. However, because

of continued

high unemployment, much of the economic potential created

by this

increase has lain idle in post-unification Germany. But at

the same time,

millions of workers have also taken on so-called

"mini-jobs", or become

"pro-forma self-employed".

Since the mid-1990s, part-time jobs of less than fifteen

hours work per

week, which are not paid above DM 620 (€ 318) per month (€

400 since

April 2003), are tax-free and also partly free of

social-security contribu-

tions and entitlements. The number of "mini-jobbers" has

increased

steadily, rising from 2.8 million in 1987 to over 4.4

million in 1992

and to 6.5 million in 1999 (ISG 1999, p. 2). In 2002, more

than 50 per

cent of "mini-jobbers" were either younger than

twenty-five or older than

fifty-five; 70 per cent were women (mainly housewives). In

this way,

mini-jobs act as stabilisers of the continental

Bismarckian social-insur-

ance state that focuses on skilled, highly paid male

breadwinners, and

which thereby results in a comparatively low female

employment rate

(M. Schmidt 1993).

Meanwhile, the incidence of "pro-forma self-employment"

(Schein-

selbstständigkeit) also increased dramatically during

the

1990s. Under

this rubric, employees of companies reclassify themselves

as self-

employed sub-contractors, thereby avoiding the payment of

social-se-

curity contributions altogether. For instance, haulage

drivers can

become formal owners of a truck financed and operated by a

freight

company or carrier. Of course, most of these self-employed

persons still

depend on an "employer", but despite government

restrictions, pro-for-

ma self-employment is growing in a number of service

industries, with

estimates ranging between 1 million and 1.4 million

Scheinselbstständige

in 2001. Clearly, the overall number of 7 million

mini-jobs and pro-

forma self-employed persons has to be seen as a

consequence of steeply

rising non-wage labour costs in the aftermath of German

unification.

The disproportionate rise in welfare recipients and, as a

consequence,

in non-wage labour costs first became apparent in 1992.

Figure 8.1 shows

that this was an effect of the so-called "unification

shock" (Sinn and Sinn

1992; Schluchter and Quint 2001), which saw Germany's GDP

per

capita drop by DM 6,000 (€ 3,077) to DM 34,990 (€ 17,943)

as a result

of the number of inhabitants growing more than economic

output. In

addition, while eastern Germany experienced massive job

losses in the

aftermath of a historically unique de-industrialisation

process (cf. chapter

2 in this volume), the western German economy, which

remained strong,

170

Roland Czada

had to shoulder the resulting social costs. Initially,

total net financial

transfers to the new Länder (consisting of special

federal

grants, EU

grants, fiscal equalisation schemes, federal supplement

grants and

social-security contributions, minus taxes and

social-security contribu-

tions collected in the east) amounted to almost 10 per

cent of GDP in the

early years, and only fell to 4 per cent towards the end

of the 1990s. Sinn

and Westermann (2001) note that the current account

deficit of the

eastern Länder amounts to 50 per cent of their GDP.

Eastern Germany's

dependency on resource imports is therefore much greater

than even that

of the south Italian Mezzogiorno, which is often referred

to as the classic

example of an essentially parasitic economy (Sinnand

Westermann 2001,

pp. 36- 37). Two-thirds of the current account deficit in

the new Länder

has been financed by public transfers; the remaining

one-third has been

met by private capital flows. Crucially, more than half of

the public

transfers have been spent on social security and only 12

per cent on

public infrastructure investments (Sinn 2000).

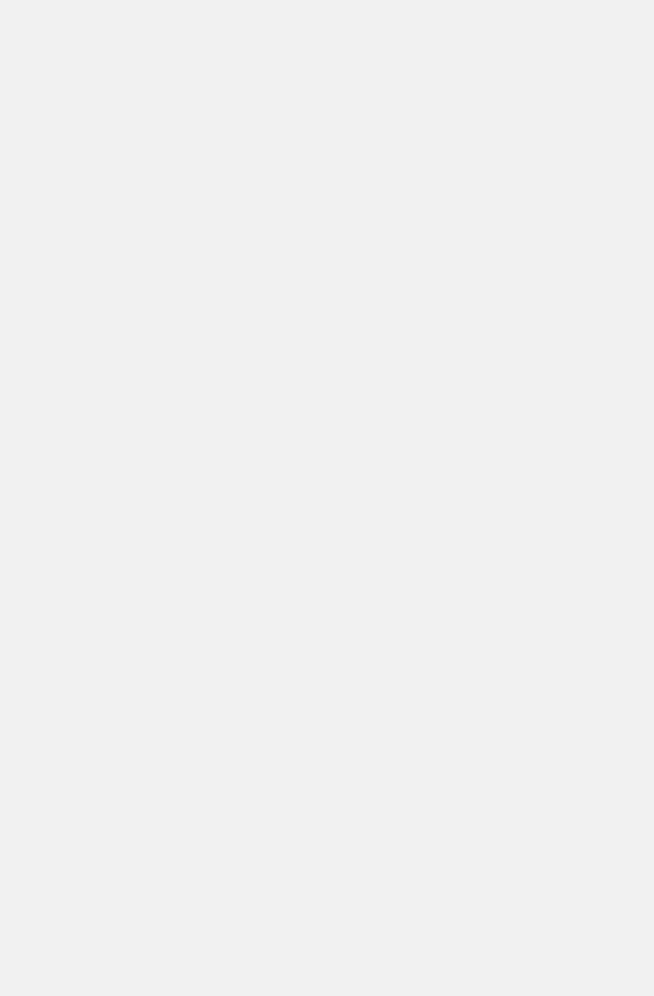

Accordingly, the social expenditure ratio, which expresses

state wel-

fare expenditure as a share of GDP, has risen sharply

after unification

(Figure 8.2). Before 1990, the social-security funds were,

generally

speaking, in good financial health, and therefore seemed

to be well

prepared for shouldering the immediate social costs of

unification. How-

ever, by 2003, the reserve had shrunk to a historic low of

just half of one

month's expenditure, thereby reaching a critical limit for

a pay-as-you-go

system. This "shrinkage" occurred despite the fact that

Germany had

increased social-security contributions on several

occasions, whereas its

competitors had all managed to reduce them.

Because of the costs of welfare, there is a considerable

difference

between salaries and take-home pay. In 1999, the "average"

production

worker took home less than half of what it costs to employ

him or her,

defined as net income plus employer's and employee's

social-security

contributions plus taxes, compared with about 70 per cent

in Britain or

the USA (OECD 2000). Growing welfare expenses and rising

labour

costs not only reduced the demand for labour, but also

slowed dispos-

able income growth. During the 1990s, even though gross

real wages per

capita increased by 2 per cent, net real wages per capita

rose by just 0.3

per cent annually. Consequently, the trade unions'

moderate wage

claims in the second half of the 1990s did not translate

into increasing

levels of employment figures, but instead only reduced the

rate of

increase of disposable income. In other words, Germany's

high welfare

burden has squeezed private consumption, which grew by

just 1.5 per

cent annually between 1991 and 2001, well below the level

achieved in

other industrialised countries.

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

171

Agenda: the Quest for a New Welfare Consensus

Before unification, a reform of the welfare state had

never seriously

been on the political agenda. Although the CDU/CSU-FDP

govern-

ment under Chancellor Helmut Kohl was in favour of a more

flexible

labour market, and implemented moderate cutbacks in

social-security

spending (cf. Figure 8.2), only minor changes were made.

Just before

the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, the

Bundestag passed a

pension reform bill to compensate for future imbalances

created by

West Germany's adverse demographic developments (cf.

chapter 9 in

this volume). The law was backed by a broad coalition of parties,

trade unions and employers,

and thus followed the traditional

consensual model of welfare politics.

In fact, and in a major change in policy, the government

planned to

cut both taxes and social-security contributions from

1990. Despite slow

GDP growth rates and still moderate unemployment figures,

public-

sector deficits had shrunk during the preceding decade.

There had also

been a sharp rise in corporate profits. In 1989, the

compulsory pension

funds noted that their cash reserves were at their highest

since the

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

Figure 8.2. Social expenditure ratio, 1980 - 2002

Source : Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Soziale

Sicherung

2004; Czada 2002, p. 160.

172

Roland Czada

introduction of the pay-as-you-go scheme. The 1989 report

of the

government's Council of Economic Advisers

(Sachverständigenrat) -

published just a few weeks before the fall of the Berlin

Wall - actually

encouraged trade unions to switch the emphasis in their

work-related

demands away from issues of quality to issues of quantity,

such as wage

levels. The rationale behind this was to boost private

consumption by

improving employees' share of the expansion in corporate

profits that

had developed hitherto (Sachverständigenrat zur

Begutachtung der ge-

samtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung 1989, p. 166). In return

for a deregu-

lation of the labour market, the unions were offered a

growth and

employment strategy based on lower taxes, lower

social-security contri-

butions and higher wages. In essence, the federal

government pursued a

corporatist strategy similar to that of the Netherlands,

which eventually

led to the widely praised "Dutch Model".

However, following unification, this strategy failed for

two reasons.

On the one hand, the reconstruction of the eastern German

economy

called for a massive increase in public spending and

private investment.

There was no longer any leeway for wages to increase and -

even more

importantly - the Bundesbank had to raise interest rates

to a historic

high in order to curb the inflationary pressures unleashed

in the post-

unification boom. Moreover, Germany, once among the

world's major

net exporters of capital, had to redirect capital outflows

to the tune of

DM 200 billion (€ 103 billion) per year in order to

finance the recon-

struction effort in the east. Interest rates remained

high, and, as noted in

chapter 1, total public-sector debt doubled within a

decade. This meant

that the demand-led growth strategy of the late 1980s was

no longer

viable for simple economic reasons.

On the other hand, there was a political impediment to

welfare-state

reforms. Unification policies started from the general

assumption that

West Germany's structures of governance did not need to be

reformed

in the process of their transfer to the new Länder

(Schäuble 1991, pp.

115-16). Based on the principle of "institutional

transfer" (Lehmbruch

1992, p. 41; see also chapter 2 of this volume), the whole

legal

and organisational system of the west had been transferred

to the

new Länder. Unfortunately, a number of West German

institutions

revealed themselves to be ill-suited to dealing with the

task of transform-

ing a socialist command economy into a capitalist market

economy. In

response, the federal government initiated a series of

legislative amend-

ments that were soon dubbed "repair laws"

(Reparaturgesetze). Remark-

ably, despite their far-reaching redistributive character,

all these laws

and consecutive amendments were passed with broad

parliamentary

majorities.

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

173

Throughout the 1990s, before the political class

recognised the need

for a more coherent reform of the country's redistributive

policies,

welfare policy was characterised by more-or-less permanent

agenda

shifts. Before the crisis of unification, few had

considered the interregio-

nal redistributive effects of social-security funds and

their consequences.

Yet Mackscheidt (1993) has shown that these have long had

a greater

impact than even the federal system's financial

equalisation schemes.

Whereas the latter had always been politically highly

controversial, the

manner in which social-security funds were channelled from

prosperous

regions to poorer ones was akin to a hidden agenda.

Interregional redis-

tributions had, since the mid-1970s, functioned as an

informal way of

supporting the restructuring of old industrial regions.

Massive resource

transfers to the new Länder, however, threatened to

overburden this

widely, if tacitly, accepted system. As a result, the top

priority for

fiscal and welfare policy shifted to increasing public

revenues and

social-security contributions, whilst simultaneously

cutting benefits.

But instead of cutting taxes and social-security

expenditure, the fed-

eral government delayed and, eventually, reversed its

plans. Moreover, it

became clear that a much more fundamental reform of the

welfare state

would be needed if its collapse was to be avoided in the

long run. Even

though the West German pension reform of the late 1980s

had already

made some provision for population decline after 2015,

unification

drastically changed this forecast. As a result of high

rates of unemploy-

ment and early retirement in the east, a stagnating

portion of economic-

ally active persons had to pay for a rapidly growing

number of pensioners

at a much earlier stage than had originally been predicted.

From the mid-1990s onwards, therefore, the federal

government tried

to forge alliances within the party system and with trade

unions, business

groups and employers' associations in favour of

far-reaching welfare-

state and labour-market reforms, most of which, as will be

discussed

below, met with failure. It was not until the new

millennium that all

the main political parties, as well as the trade unions

and employers"

associations, agreed that high labour costs (in terms of

taxes and social-

insurance contributions) had been hampering employment and

eco-

nomic growth. Consequently, welfare-state reforms have now

become

a top political priority not only for the federal

government, but also for

employers' and business associations and the unions. On 14

March

2003, Chancellor Schröder announced his "Agenda 2010"

package of

comprehensive social-policy reforms, designed to solve the

long-term

problems of the German welfare state.

In light of the decline in individual welfare entitlements

and social

expenditure ratios prior to 1990, one could be forgiven

for assuming that

174

Roland Czada

retrenchment policies framed a hidden agenda for welfare

policies ever

since the mid-1970s, and that it was only the unification

crisis after 1992

which stretched the system to breaking point. In fact, as

Seeleib-Kaiser

notes in a lucid analysis (2002), the post-unification

changes must be

seen in the context of this long-term development, the

cumulated effect

of which has been a retreat from the public guarantee of

living standards.

This principle of Lebensstandardsicherung had been "the

major achieve-

ment and leitmotiv of post-war policy ever since the

historic 1957 pen-

sion reform"! (Seeleib-Kaiser 2002, pp. 31-32). At the

same time, family

support programmes have expanded considerably, including

increased

child allowances and tax credits for families, a rising

number of childcare

facilities (albeit from a very low level in the west) and

other entitlements

such as parental leave.

Process: Decline of Party Accommodation and

Corporatist Concertation

In the West German polity, policy-making proved to be slow

and incre-

mental due to high consensus thresholds based on the

legislative veto of

the Bundesrat and macro-corporatist concertation

(Katzenstein 1987;

Lehmbruch et al. 1988). In addition, ever since the

foundation of the

Federal Republic, social policies have been characterised

by numerous

bipartite (union, employers), tripartite (state, unions,

employers) and

multipartite (insurance schemes, service providers, expert

councils, pro-

fessional associations) sectoral bodies. In this system,

major changes

could effectively only be undertaken in the context of a

grand coalition

(Katzenstein 1987; Lehmbruch 2000). However, as this

section shows,

the policy-making process in the areas of employment,

health and pen-

sions during the past decade reveals a rapid decline in

party accommo-

dation and corporatist concertation.

Employment Policies

Notwithstanding some successive minor changes to

labour-market

legislation (Arbeitsmarktförderungsgesetz, AFG), the

general direction of

employment policies remained stable throughout the 1980s.

However,

in 1993, the AFG was amended to allow contributions to the

un-

employment insurance fund to be channelled into huge

work-creation

schemes (Arbeitsbeschaffungsmaßnahmen) in the east.

As a

result, the

level of contributions to the unemployment insurance fund

had to be

raised several times during the 1990s; simultaneously, the

corporatist

Federal Labour Office (BA), which administered the funds

and the

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

175

work-creation schemes, was able to increase its power

considerably in

the field of labour-market policies. In 2002, however, a

scandal sur-

rounding rigged employment statistics prompted a

full-scale reorganisa-

tion of the BA, and the Federal Employment Agency which

emerged

from its ruins is based on a managerial approach which

includes much

lower levels of corporatism and bureaucracy (cf. chapter 5

in this

volume).

During the sixteen years of the Kohl era, "labour-market

reforms

remained a process of incremental coping mostly with

imminent finan-

cial problems" (Schmid and Blancke 2003, p. 217). It was

not until 1998

that the newly elected SPD-Green government tried to

introduce a more

comprehensive reform programme. To this end, it initially

followed the

traditional macro-corporatist concertation approach, via

the" Alliance

for Jobs, Vocational Training, and Competitiveness"

(Bündnis für Arbeit,

Ausbildung und Wettbewerbsfähigkeit) - a permanent

tripartite body com-

posed of the government, employers- and business

associations, and

trade unions. However, as chapter 7 in this volume has

shown, the

Alliance was largely a failure (cf. also chapter 6). In

addition to some

irreconcilable differences between the employers and

unions, the reso-

lution of which was not helped by the attempt to deal with

very different

policy issues within just one, top-level forum, the

federal government

had unexpectedly lost its Bundesrat majority soon after

the Alliance for

Jobs had been established. Thus the Alliance suffered not

only from a

broad policy brief which was simply incompatible with an

institutionally

segmented polity (Lehmbruch 2000, p. 98), but also from

inadequate

capacity of the federal government to act as a third-party

guarantor of

corporatist agreements (Czada 2003).

Shortly before the final failure of the Alliance for Jobs,

the government

appointed a new circle of leading unionists and employers

to examine

proposals on a more specific topic. Under the chairmanship

of Peter

Hartz, director of personnel at Volkswagen and a

long-standing member

of IG Metall, the so-called "Commission on Modern Services

in the

Labour Market" (or, more popularly, the Hartz Commission)

was set

up in 2002 to develop proposals for a new employment

exchange service

and for employment programmes geared towards competition

and

entrepreneurship. To this end, the Hartz Commission made

thirteen

separate proposals (Hartz et al. 2002). Among the most

important was

the so-called Personal Service Agency, which has now been

introduced

in all of Germany's 181 unemployment offices

(Arbeitsämter). Under the

proposal, unemployment offices or private temporary job

agencies will

employ anyone unable to find new work within six months,

with the

aim of neutralising the traditionally high levels of

protection against

176

Roland Czada

dismissal. In addition, the commission proposed the merger

of un-

employment and local authorities' social welfare offices

(Sozialämter)

into so-called "job centres", including the combination of

long-term

unemployment assistance and general income-support

payments (So-

zialhilfe). The latter has become the most controversial

element of the

Agenda 2010 reform package and was finally passed in the

Bundesrat

only on 9 July 2004 (cf. chapter 4 in this volume)..

An additional proposal by the Hartz Commission aimed to

facilitate

self-employment, by means of the so-called "Ich AG", which

sees a fixed

tax rate of between 10 and 15 per cent levied on those

self-employed

persons with an annual income of between € 15,000 and €

20,000. Many

of the proposals contained in the commission's report came

from

reform-oriented trade unionists. Walter Riester, a former

deputy leader

of IG Metall and Federal Labour Minister from 1998 to

2002, estab-

lished the commission and appointed Hartz, a former

colleague from his

union days, as its head. The largest German trade union,

Ver.di, was also

represented while commission members from industry

included repre-

sentatives from Daimler-Chrysler, BASF, Deutsche Bank and

the con-

sultancy firms Roland Berger and McKinsey. Other members

of the

commission were Peter Gasse, regional head of IG Metall in

North

Rhine-Westphalia, and his predecessor Harald Schartau, who

went on

to become minister for labour in that state.

What is striking is the way in which corporatist

negotiations at the

peak level of labour-market associations and the state

were replaced by a

newly established policy network based on SPD-affiliation,

reformist

orientation, personal reputation, experience and

expertise. Simultan-

eously, the focus on a rather more closely defined set of

problems

replaced the broad scope of issues which had characterised

the corpor-

atist emphasis of the Alliance for Jobs. In any case, the

SPD-Green

government has stuck to an open style of consensus

mobilisation focused

on "friendly" experts who are loosely associated with the

incumbent

parties. By contrast, Chancellor Kohl used his personal

networks as well

as "fire-side" talks with high-ranking business and union

representatives.

Initially, Chancellor Schröder seemed to favour a

similar

style, but

following the breakdown of the Alliance for Jobs and the

defection of

the business elite to support his challenger Edmund

Stoiber (CSU) in

the run-up to the 2002 federal election, Schröder has

refocused his

attention on experts from within the SPD or academia.

In terms of results, the new approach of "government by

commis-

sion" has had a limited impact. In addition to the

reduction of unemploy-

ment benefit (Arbeitslosengeld), which is funded from

insurance

contributions, unemployment assistance for the long-term

unemployed

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

177

(Arbeitslosenhilfe) and general income-support payments

(Sozialhilfe)

were merged with effect from 2005. As these two schemes

had been

run separately by the Federal Labour Office and local

authorities, a new

interface between labour-market institutions and municipal

poverty-

relief programmes seems to be emerging. However, this will

probably

necessitate further reforms, not least a comprehensive

reform of munici-

pal finances and the complex federal system (cf. chapter 4

in this

volume). Even though the relevant commissions have been

set up, it

was not clear in summer 2004 whether they would result in

anything

other than incremental change.

Pension Politics

Pension issues have often served as a test case for

consensus-building

capacities across party lines and on both sides of the

corporatist divide.

In West Germany, party concordance and corporatist

agreements pre-

vailed throughout the post-war era. However, as noted

above, the recur-

ring financial crises caused by a decline in the number of

contributors

and a disproportionately growing number of recipients in

eastern

Germany meant that pension politics became highly

controversial after

the mid-1990s. Table 8.2 clearly illustrates the impact of

unification, as a

result of which huge surpluses in the west will have to

compensate for

huge deficits in the new eastern states until well beyond

2016. In 2003,

an estimated € 13 billion deficit in the east contrasts

with a surplus of

€ 14 billion in the west. These reserves in the west would

have sufficed to

stabilise the pension contributions of wage earners well

below the cur-

rent level of 20 per cent of gross income in 2004. Apart

from unification-

related problems, demographic changes call for major

modifications of

the old established Bismarckian model. Starting with the

1992 reform,

subsequent pension law amendments of 1997, 1998, 1999,

2001 and

2003 have cut future pension claims considerably, thereby

paving the

way for a new system of compulsory insurance combined with

private

retirement provisions.

The pension reform of 1989, which came into effect in

1992, was

backed by a broad coalition of parties, unions and

employers, and, thus,

followed the established consensual model. Initiated

before the fall of the

Berlin Wall, the reform was intended to correct future

imbalances

caused by demographic changes in West Germany. Most

importantly,

from 1993 onwards, pensions were to be adjusted in line

with increases

in annual net income and not, as had been the case

previously, with

increases in earnings. This measure was to prevent

pensions in the future

178

Roland Czada

from exceeding 70 per cent of the average net income of

active wage

earners (the net replacement rate).

However, the combined effects of unification, mass

unemployment

and early retirement meant that further reforms soon

became necessary,

1

and in June 1996, a Commission on the Further Development

of the

Pension System was established. Following its

recommendations, the

CDU/CSU-FDP government legislated for a further gradual

reduction

in the net replacement rate for standard pensions from 70

to 64 per cent

between 1999 and 2030. This time, the SPD opposition,

backed by the

Table 8.2. Net balances of the compulsory pension fund

financed equally by employees and

employers, 1999 - 2016 (€ billion)

a

Net balance (expenses minus revenues)

Year

Western Lä

nder

Eastern Laä nder

All Germany

1999

9.3

-4.4

4.9

2000

6.5

-5.9

0.6

2001

6.5

-6.5

0.0

2002

9.7

-13.4

-3.8

2003

14.5

-13.2

1.3

2004

15.4

-13.6

1.8

2005

15.2

-14.0

1.3

2006

15.1

-14.2

0.9

2007

15.1

-14.2

0.9

2008

15.6

-14.5

1.1

2009

16.0

-14.9

1.0

2010

16.7

-15.3

1.4

2011

16.6

-16.0

0.6

2012

15.8

-16.7

-0.9

2013

17.4

-17.1

0.3

2014

18.8

-17.7

1.1

2015

19.4

-18.4

1.0

2016

20.9

-19.1

1.8

Note:

a

2002 - 16 forecast.

Source: Bundestagsdrucksache 15/110, pp. 62, 111-12.

1

With an additional 800,000 persons taking early

retirement, pension funds have had to

pay out an extra DM 20 billion (€ 10.3 billion) since

1992. The pension payments for 4

million pensioners in the new Länder amounted to DM

75

billion (€ 38.5 billion) between

1992 and 1997. Therefore, additional costs of DM 37

billion (€ 19 billion) per annum,

which had not been anticipated in the preceding reform,

have had to be borne by wage

earners, pensioners and the state.

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

179

unions, put up fierce resistance - not least because of

the federal elec-

tions that were just ten months away at the time of the

bill's passage

through parliament. On 11 December 1997, the first piece

of pensions

legislation since the foundation of the Federal Republic

not to be agreed

by a broad cross-party majority passed the Bundestag.

After its election

victory in 1998, one of the first acts of the SPD-Green

government was

to suspend the 1997 pension reform. Here was another

novelty in post-

war welfare politics which casts doubt on whether

Katzenstein's portrait

of "policy stability even after changes of government" is

still valid (1987,

pp. 4, 35).

The politics surrounding pension reform in 1997 and 1998

only

foreshadowed future party dissent and programmatic

volatility. Indeed,

the "Jekyll and Hyde" years in the politics of pensions

were still to come:

in 1999, fiscal problems forced the SPD-led government to

revert to the

austerity measures of its conservative predecessors.

Reneging on its

election promises, the SPD planned to replace the wage

indexation of

pensions by price indexation for a certain period to lower

the replace-

ment ratio from 70 to between 67 and 68 per cent. In 2000,

the

government published yet another reform proposal, which

not only

exceeded the planned cuts of the previous CDU/CSU

government, but

was also likely to change the system's basic operating

principles. Apart

from a radical reduction in benefit levels, it introduced

a private statu-

tory pension scheme that would in the long run have

gradually trans-

formed the corporatist Bismarckian pay-as-you-go system

into a fully

capital-based pension. The so-called Riester-Rente, or

Riester pension,

named after the then Federal Minister for Labour and

Social Affairs,

Walter Riester, met with a barrage of criticism from the

CDU/CSU and

the trade unions. Again, the unions' wholehearted support

for a CDU/

CSU position in a highly controversial area of welfare

policy was quite a

novel experience. The unions were particularly opposed to

the fact that

the shift towards a private mandatory pension fund

signalled a departure

from the traditional joint financing of pensions by

employees and em-

ployers. The CDU/CSU opposition initially even rejected

those parts of

the government bill which were in line with their own

former plans and

pre-election statements. As a consequence, the SPD-Green

government

had to trim the reform package so that it was no longer

subject to

Bundesrat approval. What is more, the SPD was forced into

making

substantial concessions to its own left-wingers just in

order to secure

the government's Bundestag majority.

The pension reform in 2000 and 2001 was, therefore, an

example of

semisovereignty without consensus, which made the parties

in govern-

ment vulnerable to all kinds of pressure from within their

own ranks.

180

Roland Czada

Nonetheless, the reform initiated a mixed pension system,

composed of

a reformed pay-as-you-go compulsory pension scheme and a

new pri-

vate, but non-mandatory, pension. The private component

gives em-

ployees the option of contributing up to 4 per cent of

their earnings by

2008 into company or other private schemes. Employees can

invest in a

range of schemes offered by private insurers, including

private-pension

insurance organisations, investment funds, life insurance

funds, and

savings banks. All private pensions must meet certain

criteria before

employees are eligible for state subsidies and tax

exemptions, and -

contrary to the Bismarckian tradition - all benefits will

be taxable. The

incentives and subsidies for making contributions to

private accounts are

targeted at lower-income individuals and families. Pension

credits

earned during a marriage can be shared equally by both

spouses through

a new pension-splitting option. The government also

introduced reforms

to improve old-age security for women, including

compensation for

reduced earnings during child-raising years, and granting

pension credits

to mothers who could not pursue part-time employment.

Despite its departure from the established model, the 2000

pension

reform was still ultimately incremental in its impact and

failed to address

the long-term financial problems caused by demographic

change. In

November 2002, a new Commission for Sustainability in the

Financing

of the Social Security System under Professor Bert

Rürup

(the so-called

Rürup Commission) was set up in order to address yet

again

the long-

term financial aspects of the pensions and health-care

crisis. Its recom-

mendations included a gradual increase in the retirement

age between

2011 and 2035 from the current level of sixty-five to

sixty-seven, penal-

ties for early retirement and a reduction in the annual

increases in

pension payments. A majority of the twenty-six commission

members,

consisting of experts who were generally close to the

SPD-Green gov-

ernment, backed the final report's recommendations to

safeguard inter-

generational justice and limit future pressures on the

social-insurance

systems. Only commission members affiliated to the trade

unions

opposed the proposals.

In August 2003, the Rürup Commission calculated that

the

combined

effect of the 1989 and 1992 reforms was already to reduce

the real value

of pensions by 30 per cent in 2030. On top of that, the

Riester reform of

2000 imposed a further cut of 7 per cent, while an

increase in the general

retirement age will mean another 3 per cent reduction. In

other words,

from the viewpoint of 2003, the average pension benefits

in 2030 will be

40 per cent lower than they would have been under the

pre-1989 rules

(Berliner Zeitung, 9 August 2003). This means that

supplementary pri-

vate pension provision has become indispensable for anyone

below the

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

181

age of fifty. The reduction in benefits combined with an

increase in

funding from general taxation has also meant that the

premiums for

the compulsory pension insurance could be cut from 20.3

per cent of

gross income in 1999 to 19.5 per cent in 2003. This

saving, along with

state bonuses, is meant to be invested into private or

company pension

plans. In summary, the era of the all-embracing,

Bismarckian work-

related compulsory insurance schemes aimed at status

security is over.

So far, however, the public has not yet shown a great

awareness of this

new mix of compulsory and private provisions, since this

will only fully

affect those generations of pensioners who are still to

come.

Health Care

The German health-care sector still constitutes a classic

example of

semisovereignty. Because federal and state governments

share legislative

authority, the Bundesrat has been involved in all fields

of general health

legislation. In addition, a large number of other actors

dominate the field,

such as various organisations of insurers, service

providers (doctors and

hospitals), pharmaceutical producers, consumers and their

respective

peak associations (cf. Döhler and Manow 1967). The

process

of formu-

lating health policy has always been guided by networks of

experts, many

of them linked to the main peak associations. A host of

advisory bodies,

commissions and consultative meetings are part of the

decision-making

process. As a result, the incremental "muddling through"

approach which

has befallen most health-care reforms can be traced to an

early stage in

the policy cycle, and not usually to the constitutional

vetoes embedded in

the federal structure. In fact, most health-care

legislation during the past

decades did not implement any restructuring of the

institutional relation-

ship between health insurers, providers and the insured.

Modest co-

payments for medications, dental treatment,

hospitalisation and other

items were introduced in 1982. These payments were further

increased

by the Health Care Reform Act of 1989 and again by the

Health Care

Structural Reform Act passed in 1992. The latter

introduced new regu-

latory instruments, which included the reorganisation of

the governance

of health insurers and a cap on medication costs and

prospective hospital

payments. In addition, it proposed measures to overcome

the separation

between out-patient medical care and hospital care that

prevailed in the

old Federal Republic, and it introduced a free choice of

health funds for

the insured (Blanke and Perschke-Hartmann 1994).

Politically, the law rested on the famous 1992 Lahnstein

compromise

between the CDU/CSU and the SPD. This excluded the liberal

FDP,

even though the latter was in government with the CDU/CSU.

The

182

Roland Czada

reform was a partially successful attempt to reduce the

institutionalised

power of the medical profession and the pharmaceutical

industry, both

of which have traditionally been protected by the FDP. The

Lahnstein

compromise was part of a stream of informal consensual

policy-making

that was characteristic of the immediate post-unification

period (Manow

1996). However, this was followed by a period of

intensified party

conflict, conceptual volatility and political stalemate.

Most of the reforms passed between the mid-1980s and 2000

at-

tempted to redistribute the increasing cost burdens

between the various

stakeholders. There was no intention, as in old-age

pension policies, to

alter the balance between public and private insurance

schemes. Though

the health sector is characterised by fierce competition

between hos-

pitals, doctors and pharmaceutical companies, and though a

number of

new competitive elements have been introduced, a

health-care market

based on privately financed products and services has

never developed.

Moral hazard, information asymmetries and cherry-picking

became even

worse after the strict corporatist order had been

loosened, and once the

insured were able to exercise some degree of freedom in

their choice of

insurance fund.

Most stakeholders agree that the severe inefficiencies in

the health-

care system are caused by fragmentation, duplication and

overlap, and

accordingly, recent health-care reform acts have tried to

integrate the

different levels and sectors of care. For instance, free

contracts between

insurance providers and rehabilitation clinics have been

allowed and

even encouraged in order to overcome the division between

funding

agencies and care providers. The health-care system still

rests on the

basic assumption that everybody should be entitled to

receive all the

necessary services, and that the doctors should decide

what is necessary

for their specific patients. It is only recently that the

issue of prioritisation

has arisen. The long-established "Federal Committee of

Panel Doctors

and Sickness Funds" is now expected to provide

authoritative definitions

for measures of quality assurance, as well as developing

criteria for

whether certain diagnostic and therapeutic services are

appropriate.

However, its attempts to impose a ceiling on expenditure

for drugs and

medication fell foul of European cartel laws, and were

declared unlawful

following a case brought by Germany's powerful

pharmaceutical indus-

try. In 2003, plans to establish a National Centre for

Medical Quality

again met with fierce resistance from physicians and the

pharmaceutical

industry, who decried the proposals as leading straight

back to GDR

socialism.

Traditionally, quality assurance issues have been in the

domain of

individual physicians and organisations and recent debates

on such

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

183

issues have to be seen in the context of a renewed

increase in health-care

expenditure - mainly as a result of the abolition of

spending caps for

medicines. The corresponding rise in contribution rates

from 13.5 per

cent to 14 per cent of pre-tax income brought cost

containment back

onto the agenda in 2002.

In 2003, a new informal "grand coalition" on health

emerged between

the governing SPD and the opposition CDU/CSU, with the aim

of

cutting health benefits again and further limiting the

sector's regulatory

autonomy. In a rare show of unity, the unions and

employers' associ-

ations even called for the abolition of the statutory

regional associations

of accredited physicians (ärztekammern), which act as

clearing houses

between individual doctors and the statutory health funds,

thereby re-

moving care providers from the scrutiny of the insurance

funds. As the

1992 Lahnstein compromise had illustrated, a grand

coalition in health

policy can overcome the bicameral legislative veto and

also withstand

pressures from well-organised groups, such as insurance

funds, phys-

icians and pharmaceutical firms. Once again, however, the

new inter-

party consensus agreed in 2003 led neither to

institutional reform nor to

the prioritisation of certain treatments and medicines.

Instead, new

market-like incentives were introduced, including the

removal of sick

pay from the bipartite-financed compulsory schemes.

Patients are now

expected to pay € 10 for each quarter in which they visit

the general

practitioner (GP) (the so-called Praxisgebühr).

Indeed,

the "gatekeeper"

function of GPs will be strengthened, as specialists must

collect another

€ 10 if patients cannot present a referral letter. Other

plans include

additional co-payments for dentures, reductions in

maternity benefits

and death grants, and cuts in benefits for parents nursing

sick children.

Even though this has meant at least a temporary

improvement in

the financial position of the health-insurance funds, such

measures,

and especially the Praxisgebühr, remain deeply

unpopular

among the

population (Die Welt, 31 July 2004).

In health policy, governments have continued to rely on

benefit cuts

and incremental measures like budgeting, co-payment and

competitive

incentives for the various stakeholders. Only recently

have prominent

politicians of all parties called for a more fundamental

reform in order to

address the permanent crisis in health policy, with a

universal compul-

sory health-insurance scheme for all citizens supplemented

by voluntary

private insurance contracts (Bürgerversicherung)

being the

preferred

model. Inevitably, the chances for a fundamental systemic

change are

still small, not despite, but because of, recurring grand

coalitions in

health politics.

184

Roland Czada

Consequences: Erosion of Self-Governance and New

Forms of Intermediation

The institutional segmentation of the West German

political system has

been emphasised, in particular, by Gerhard Lehmbruch and

Fritz

Scharpf. Lehmbruch pointed to incompatibilities of party

competition

and co-operative federalism (Lehmbruch 2002), whereas

Scharpf's re-

search on "policy interlocking" and the "joint

decision-making trap"

offered a key explanation of failed policy reform

initiatives in different

sectors (cf. Scharpf 1988). Peter Katzenstein's (1987)

seminal work on

"semisovereignty" struck a similar chord; however, in

contrast to Lehm-

bruch and Scharpf, he praised as a virtue what they had

both considered

to be a design fault.

Yet it is doubtful whether either of these models can

adequately

account for the overall stable course of welfare policies

during the

1980s. Throughout this decade, the CDU/CSU-FDP government

com-

manded a comfortable majority in the Bundesrat, and from

1982 to

1990, this arguably made the Kohl government the most

sovereign

compared with all its predecessors and successors in

office (cf. chapter

3 in this volume). Even during the 1950s, the Adenauer govern-

ment lost its Bundesrat majority for a few months (March

1956 -

January 1957). The political issue of divergent majorities

in the bicam-

eral legislature did not emerge until after the 1972

federal election (cf.

Figure 8.2 in this volume). By contrast, the CDU/CSU-FDP

coalition after 1982 held a majority of five to thirteen

votes in the

Bundesrat throughout the 1980s; it was not until the Lower

Saxony

election in 1990 that things changed. Thus, with a solid

Bundestag

majority and markedly weakened labour unions (after

unemployment

figures exceeded one million in 1981), Kohl was presumably

the most

powerful chancellor since Adenauer.

To explain why policy remained so stable during the 1980s,

one

therefore has to focus on a range of factors outside the

domain of

the constitutional veto structures. By stressing the deep

fears within

the Kohl government that welfare cuts could adversely

affect its electoral

performance, Zohlnhöfer (2001b) has cast some doubt

on the

exclusive

validity of the institutional explanation provided by

Scharpf and

Lehmbruch. A second important factor was the strength of

the CDU's

social-catholic wing, which was led by Norbert Blüm,

a

self-confessed

defendant of the welfare-state consensus. As Federal

Minister for

Labour and Social Affairs in every single Kohl cabinet

(and therefore

in charge of the largest spending ministry), he was able

to make full use

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

185

of the principle of ministerial autonomy (Ressortprinzip)

to act as a

powerful stalwart of the Bismarckian welfare state from

1982 until the

advent of the Schröder government in 1998.

The anatomy of neo-liberal strategic policy changes in the

UK,

Sweden and the Netherlands shows that problem load is an

important

predictor of policy change. The "pain threshold" above

which parties and

governments in those countries felt forced to act,

irrespective of their

ideological backgrounds, had not been reached, by any

stretch of the

imagination, in West Germany before 1990. Bearing all that

in mind -

the solid majority of the Kohl government in both

chambers, prevailing

electoral considerations against benefit cuts, a powerful

unionist pro-

welfare wing in the CDU, and the moderate problem load of

the time -

constitutional veto potentials cannot explain the course

of welfare-state

reform during the 1980s. This becomes even more apparent

when the

welfare policies of the 1980s are compared with those of

the following,

post-unification decade.

But here too, an explanation focusing on formal veto

powers fails to

account for the delay in cutting social-security

contributions and income

taxes which the federal government had planned in 1989. On

the con-

trary, the early 1990s have been characterised as the last

triumph of

corporatism, party concordance and co-operative federalism

(Sally and

Webber 1994; Lehmbruch 2000). Even though the Kohl

government

had grown stronger as a consequence of its electoral

dominance in the

new (eastern) Länder, and even though the Länder

had

temporarily sus-

pended their constitutional rights in order to approach

unification prob-

lems in a united and flexible manner, the federal

government actively

sought to include key representatives of business, unions,

the Länder and

the SPD opposition in a range of fora. In particular, the

SPD had been

incorporated into the newly established unification policy

network with

the Treuhandanstalt (THA) as its focal point (see chapter

5 in this

volume). Prominent SPD figures such as Klaus von Dohnanyi

and Detlef

Karsten Rohwedder, as well as union leaders such as Franz

Steinkühler

and Dieter Schulte, had been appointed to high-ranking

positions within

the THA's executive, supervisory and operative structure.

As a result, the early 1990s witnessed something of a

temporary revival

of large-scale inter-party consensus and corporatist

politics. The usual

segmented policy-making had been bypassed for a while, at

least until

1992, when the first signs of the severe economic crisis

caused by

unification prompted an examination of the original

concept of a

market-led transformation process and institutional

transfer.

The 1990s were, undoubtedly, an active period in terms of

agenda

shifts and health reform in particular (Kania and Blanke

2000). After

186

Roland Czada

decades of corporatist policy-making and its last triumph

in the imme-

diate post-unification period, the following years brought

a crisis of

consensus politics and corporatist self-government. To

draw a conclu-

sion from a political-science perspective, the German

welfare state of

2003 was characterised by more state intervention and more

market

elements than the one Katzenstein described in 1987. State

regulation

and tax-financed state subsidies increased, as did

co-payments of the

insured and the share of private insurance contracts,

while the share of

the Bismarckian wage-related compulsory insurance

contributions de-

creased. Most remarkable, however, is the rapid loss of

self-governabil-

ity - and its requisite associational capacities. Germany

is no longer "a

good example of how government can enact the rules and

then leave the

doctors and sick funds to carry out the programme with

little interven-

tion" (Glaser, quoted in Katzenstein 1987, p. 184). The

same is true

for other fields of social policy because of increased

conflicts among

stakeholders over their share of a shrinking pie.

But even so, Katzenstein's assertion (1987, p. 192) that

"a closely knit

institutional web limits the exercise of unilateral

political initiatives by

any one actor" continues to hold true. Whether this

continues to encour-

age incremental policy changes, as it did in times of

affluence, has

become a moot point. The 1990s were characterised by

sequences of

political stalemate and a deepening of state involvement

rather than

corporatist incrementalism. The latter depends not only on

consensual

policy-making. Making semisovereignty work requires strong

commit-

ments among and within organisational actors participating

in sectoral

self-governance. Without the peak associations being able

to commit

their organisational substructure and their individual

members to make

their resources available in support of corporatist

arrangements, consen-

sus is almost irrelevant since it cannot translate into

viable policies. The

creeping decentralisation of the industrial-relations

system, both in

terms of lower membership density and adherence to the

principles of

collective bargaining, seems to be one of the main

problems in this

respect (Ebbinghaus 2002a ; see also chapters 2 and 7 in

this volume).

These far-reaching changes within the industrial-relations

system sug-

gest that the German combination of a "decentralised

state" and a "cen-

tralised society" emphasised by Katzenstein (1987) is no

longer valid.

German organised capitalism has decentralised very

rapidly, at least in

regard to labour-market associations, because of the

industrial-relations

crisis in the east and because of a generational change in

business

and union elites. The argument that such a development

towards

""social disorganisation" has been sparked off by a

combination of post-

modernism, individualisation and the effects of

globalisation (Beck

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

187

1996) may constitute part of the explanation, but it

cannot account for

some specificities of the German case. First, this

argument neglects the

reform plans of the pre-unification Kohl government, which

resembled

the Dutch and Swedish concepts and could not be realised

in the post-

unification period. Germany's political economy and

welfare state would

quite simply look entirely different if unification had

not occurred.

Second, global market pressures did not normally weaken,

but rather

sustained corporatist capacities in Germany and other

European coun-

tries (Katzenstein 1985). Third, the industrial-relations

crisis did not

emanate from big global firms, but from the small and

medium-sized

industries of eastern Germany in particular. The export

industry is still

interested in industry-wide collective bargaining which

protects it

against excessive wage demands. In contrast small firms

often cannot

afford wages paid in the big export industries, and,

therefore, prefer

decentralised bargaining structures. It is for this reason

that industry-

wide bargaining has persisted in big firms, and therefore

still covers a

majority of employees. When it comes to political

representation, how-

ever, small and medium-sized enterprises are stronger, a

result princi-

pally of their privileged access to the Land level of

government and

via the statutory chambers of trade and industry

(Industrie und

Handelskammern).

In contrast to its centralised Swedish, Dutch or Austrian

counterparts,

the German federal government failed to forge a

corporatist deal with

the industrial peak organisations, because it was unable

to guarantee that

such an arrangement would be implemented appropriately

(Czada

2003). Towards the end of the 1990s, unions and employers

became

increasingly aware that reform packages agreed in the

corporatist arena

would have been jeopardised in the legislative process.

The Bundestag

opposition, through its Bundesrat majority, could jointly

govern the

country alongside the elected government. Indeed, it tried

to do so in

the pre-election year 1997, and again, in particular,

after 1998. It must

be remembered that it was much easier to bypass such

institutional

gridlock in the era of the "two-and-a-half" party system,

which generated

only three possible coalition strategies. After 1990, in a

system with

five relevant parties, sixteen Länder and a state of

perpetual election

campaigning, this all became much harder to achieve.

Since the mid-1990s, then, corporatist incrementalism has

suffered

from institutional segmentation, as well as from the

decreasing capacity

of the peak associations to commit their members to a

particular course

of action. In addition, the main parties have found it

much harder to

bypass these obstacles via a cross-party consensus. In

consequence,

Chancellor Schröder has adopted new strategies to

circumvent potential

188

Roland Czada

legislative vetoes as well as gridlocks in the corporatist

arena. In particu-

lar, the SPD-Green government has attempted to

short-circuit the es-

tablished policy communities in health, pensions, the

labour market and

social assistance through the deliberate use of special

commissions.

True, their role as advisory bodies in the German

political system is in

no way new and all major welfare reforms have, so far,

been accompan-

ied by special commissions. The Schröder government,

however, used

them as a device to channel the political debate, to test

public opinion,

and to exert pressure on the opposition and Länder

governments as well

as on interest associations. The replacement of classic

corporatism by

expert and stakeholder committees appointed by the federal

government

might be considered to be an appropriate way to strengthen

its authority

in times of institutional and conceptual uncertainty.

Given the imple-

mentation of the Hartz proposals and the influence of both

the Hartz

and Rürup Commissions on the Agenda 2010 reform

debate,

the shift

to government by commission has had a substantial impact.

Like para-

public institutions, the commissions serve as "political

shock absorb-

ers". Moreover, the government's authority to set up,

recruit and

dissolve them opens up much more direct mechanisms of

control than

corporatist negotiations allowed for.

Studies on the "new politics" of the welfare state (e.g.

Pierson 1996)

have emphasised the constraints in dealing with policy

change, structural

reform and retrenchment issues. Institutional path

dependencies and the

popularity of welfare programmes are said to result in the

need for

policy-makers to take small steps, and to follow

"blame-avoidance" strat-

egies. Semisovereignty, party concordance and corporatist

intermedi-

ation as described by Katzenstein (1987) have long been

best suited to

that kind of incremental adjustment: indeed, the "Bonn

Republic" was

quite successful in that respect. The new "Berlin

Republic", however, has

experienced a decline in social partnership, shrinking

capacities of asso-

ciational self-governance, and intensified party

conflicts. Potential

blockades and uncertainties of the policy-making process

have resulted

from changes in the party system, fluctuations in

industrial governance,

and the transformation of the structure of the state. The

latter has

included a reinvigoration of the regulatory state and

governmental ini-

tiatives to be found not only in social policy, but in

many other policy

Social Policy: Crisis and Transformation

189